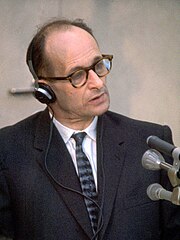

Eichmann in 1961 on trial in Israel

The most important factor is that to know Hannah Arendt, one has to know what kind of family she came from.

At this point, I doubt if Hannah knew what he was even charged with specifically, or anything about Israel's creation and why.

We need to know that after 1937 the lord mayor and the state commissioners of Hanover were members of the NSDAP (Nazi party). A large Jewish population then existed in Hanover. In October 1938, 484 Hanoverian Jews of Polish origin were expelled to Poland, including the Grynszpan family. However, Poland refused to accept them, leaving them stranded at the border with thousands of other Polish-Jewish deportees, fed only intermittently by the Polish Red Cross and Jewish welfare organisations. The Grynszpans' son Herschel Grynszpan was in Paris at the time. When he learned of what was happening, he drove to the German embassy in Paris and shot the German diplomat Eduard Ernst vom Rath, who died shortly afterwards.

Her father, Paul Arendt (1873-1913) engineer, died when she was 7, but she was raised in a politically progressive, secular family, so I take it that after her father died, the practice of Judaism was forgotten by her mother. The Arendts had reached Germany from Russia a century earlier. Usually, Jews moved from Germany to Russia for reasons of anti-Semitism and the political scene of what county owns what land at the moment.

Hannah's extended family contained many more women, who shared the loss of husbands and children. Hannah's parents were more educated and politically more to the left than her grandparents. The young couple became members of the Social Democrats, rather than the German Democratic Party that most of their contemporaries supported. Paul Arendt was educated at the Albertina (University of Königsberg). Though he worked as an engineer, he prided himself on his love of Classics. He collected a large library, in which Hannah immersed herself. Martha Cohn, a musician, had studied for three years in Paris.

Arendt's grandparents were members of the Reform Jewish community there. Hannah's paternal grandfather, Max Arendt (1843–1913), was a prominent businessman, local politician, one of the leaders of the Königsberg Jewish community and a member of the Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens (Central Organization for German Citizens of the Jewish Faith). Like other members of the Centralverein he primarily saw himself as a German and disapproved of the activities of Zionists, such as the young Kurt Blumenfeld (1884–1963), who was a frequent visitor to their home and would later become one of Hannah's mentors.

Hannah, therefore, was not only a Reform Jewess, but had become secular as well. A part of her family had been against Zionism.

Hannah Arendt married Günther Stern in 1929, but soon began to encounter increasing anti-Jewish discrimination in 1930s Nazi Germany. In 1933, the year Adolf Hitler came to power, Arendt was arrested and briefly imprisoned by the Gestapo for performing illegal research into antisemitism in Nazi Germany. On release, she fled Germany, living in Czechoslovakia and Switzerland before settling in Paris.

Hannah Arendt attended six weeks of the five-month trial with her young cousin from Israel, Edna Brocke. On arrival she was treated as a celebrity, meeting with the trial chief judge, Moshe Landau, and the foreign minister, Golda Meir.

In her subsequent 1963 report, based on her observations and transcripts, and which evolved into the book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, most famously, Arendt coined the phrase "the banality of evil" to describe the phenomenon of Eichmann. She, like others, was struck by his very ordinariness and the demeanor he exhibited of a small, slightly balding, bland bureaucrat, in contrast to the horrific crimes he stood accused of. He was, she wrote, "terribly and terrifyingly normal."

She examined the question of whether evil is radical or simply a function of thoughtlessness, a tendency of ordinary people to obey orders and conform to mass opinion without a critical evaluation of the consequences of their actions.

Arendt's argument was that Eichmann was not a monster, contrasting the immensity of his actions with the very ordinariness of the man himself. Eichmann, she stated, not only called himself a Zionist, having initially opposed the Jewish persecution, but also expected his captors to understand him. She pointed out that his actions were not driven by malice, but rather blind dedication to the regime and his need to belong, to be a "joiner." She said he was banal. (so lacking in originality as to be obvious and boring).

Hitler and Himmler reviewing Hitler's personal guards. Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

A few months after the Nazi seizure of power in Germany in January 1933, Eichmann lost his job due to staffing cutbacks at Vacuum Oil. The Nazi Party was banned in Austria around the same time. These events were factors in Eichmann's decision to return to Germany.

Nazi Germany used violence and economic pressure to encourage Jews to leave Germany of their own volition; around 250,000 of the country's 437,000 Jews emigrated between 1933 and 1939. (My own uncle by marriage, Werner Oster, managed to just

make it out in May of 1939, before they closed the door.)

Eichmann travelled to British Mandatory Palestine with his superior, Herbert Hagen, in 1937 to assess the possibility of Germany's Jews voluntarily emigrating to that country, disembarking with forged press credentials at Haifa, whence they travelled to Cairo in Egypt. He went undercover as a journalist.

There they met Feival Polkes, an agent of the Haganah, with whom they were unable to strike a deal. Polkes suggested that more Jews should be allowed to leave under the terms of the Haavara Agreement, but Hagen refused, surmising that a strong Jewish presence in Palestine might lead to their founding an independent state, which would run contrary to Reich policy. Eichmann and Hagen attempted to return to Palestine a few days later, but were denied entry after the British authorities refused them the required visas. They prepared a report on their visit, which was published in 1982.

Long before the “Final Solution” was conceived at the Wannsee Conference, Hitler and the upper echelon of the Nazi regime had hoped to resolve the “Jewish problem” through forced emigration of the Jews living in Germany. Almost three years before the outbreak of World War II, in 1937, a nondescript German bureaucrat by the name of Adolf Eichmann was sent on a covert visit to Mandatory Palestine, together with his direct supervisor in the Nazi party’s intelligence service (the notorious SD), in order to explore the possibility of deporting Germany’s Jews to the region.

On February 13, 1940, Eichmann organized a forced emigration of the Stettin Jews, of which 230 were killed during the operation.

In 1941, Eichmann recommended to use Zyklon B in Auschwitz. (There it is. He came up with killing Jews to get rid of them. At this time, the extermination of Jews had not yet started. On September 13, 1941, Eichmann contacted Rademacher (Foreign Affairs) to discuss the fate of about 8,000 Jews from Serbia. As Eichmann was unable to find a solution regarding their destination, he chose to let them shoot all.

On October 10, 1941, Eichmann and Himmler met to discuss about the Final Solution. After the Wannsee Conference (January 20, 1942) – Eichmann consigned all that had been said – He coordinated the Final Solution with the help of his assistants: Alois Brunner, Theodor Dannecker, Rolf Günther and Dieter Wisliceny.

On July 10, 1942, Eichmann answered Dannecker who asked him what to do with the 4,000 children of the Drancy camp that they should all be deported as soon as the railway convoys would be organized.

On August 1, 1942, he ordered to all SD representatives in Brussels (Belgium) to deport all stateless Jews. Even when Himmler ordered to cease gassing at the end of the war, Eichmann felt strong because he was supported by Kaltenbrunner. He played a central role in the deportation of the Hungarian Jews.

After the war, he fled to Argentina but the Israeli secret services spotted him and Eichmann was captured and brought to Jerusalem to be judged. The trial had a big impact throughout the world.

Hannah Arendt followed all the sessions and wrote a book on Eichmann’s process in which he appears as a typical “office criminal”. The trial allowed many Holocaust survivors and witnesses to tell what they had experienced. The charges were composed of 15 different crimes to be prosecuted. One of them was crime against the Jewish people (which was not mentioned during the Nuremberg Trial in 1946) and crime against humanity. Eichmann was hanged on June 1, 1962.

Arendt's five-part series "Eichmann in Jerusalem" appeared in The New Yorker in February 1963 some nine months after Eichmann was hanged on 31 May 1962. By this time his trial was largely forgotten in the popular mind, superseded by intervening world events. However, no other account of either Eichmann or National Socialism has aroused so much controversy.

Prosecution Team at Eichmann's TrialPrior to its publication, Arendt was considered a brilliant humanistic original political thinker. However, her mentor, Karl Jaspers, warned her about a possible adverse outcome, "The Eichmann trial will be no pleasure for you. I'm afraid it cannot go well". On publication, three controversies immediately occupied public attention:

1. the concept of Eichmann as banal

2, her criticism of the role of Israel and

3. her description of the role played by the Jewish people themselves.

I. The Nazi goal was to kill all Jews worldwide.

II. Israel was created as the only Jewish state in the world, a refuge for the discrimination against them worldwide

III. The Jews themselves were able to testify to the world the cruelty and inhumaneness they endured. Arendt criticized the victims!

Can one do evil without being evil? This was the puzzling question that the philosopher Hannah Arendt grappled with when she reported for The New Yorker in 1961 on the war crimes trial of Adolph Eichmann, the Nazi operative responsible for organizing the transportation of millions of Jews and others to various concentration camps in support of the Nazi’s Final Solution.

In Judaism, Good, means: pleasing in the eyes of the Lord. Evil, means: displeasing in the eyes of the Lord. What the Divine Order has determined as ultimately advantageous or harmful by man. This touches the roots of religion. In the view which considers all opposition or phenomens of variety to be mere illusion, the problem is merely denied. On the other hand, it is resolutely tackled by Zoroastrianism which poses 2 primeval principles: Good and Evil=light and darkness, locked in mortal combat. Dualism results from a logically consistent and ethically perfect good G-d. Judaism rejected this solution in the pointedly polemical utterance of Isaiah (45:7)"I form the light and create darkness: I make peace and create evil. I am the Lord that doeth all these things." Only in a monotheistic religion does the problem of the origin and continued existence of evil become acute.

Arendt found Eichmann an ordinary, rather bland, bureaucrat, who in her words, was ‘neither perverted nor sadistic’, but ‘terrifyingly normal’. He acted without any motive other than to diligently advance his career in the Nazi bureaucracy. Eichmann was not an amoral monster, she concluded in her study of the case, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963). Instead, he performed evil deeds without evil intentions, a fact connected to his ‘thoughtlessness’, a disengagement from the reality of his evil acts. Eichmann ‘never realised what he was doing’ due to an ‘inability… to think from the standpoint of somebody else’. Lacking this particular cognitive ability, he ‘commit[ted] crimes under circumstances that made it well-nigh impossible for him to know or to feel that he [was] doing wrong’.

Isn't this amoral behavior? Lacking a moral sense; unconcerned with the rightness or wrongness of something. Amorality, consists in a person's not having any moral beliefs at all- i.e. for any given act (or kind of act), such a person neither believes. that it is morally wrong nor that it is not morally wrong. Can't we say this about every Nazi that was involved in the Holocaust of World War II?

Portrait of Adolf Eichmann. SS-Obersturmbannführer Karl Adolf Eichmann (1906-1962) was head of the Department for Jewish Affairs in the Gestapo from 1941 to 1945 and was chief of operations in the deportation of three million Jews to extermination camps.Photo credit: USHMM

Eichmann was one of the major players, a leader in the organization of it all. He was responsible for many many deaths of which turned out to be 6 million of them.

Whatever had happened to Hannah's moral compass that she could not see the evil in Eichmann's actions? Anyone that went along with Hitler joined in his evil deeds. Evil Shmevil, it's all bad.

Updated on 6/27/22

Resource:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannah_Arendt

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolf_Eichmann

https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/en/document/eichmann-1906-1962-adolf.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanover

https://spartacus-educational.com/Gunther_Stern.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_K%C3%B6nigsberg

https://www.historyplace.com/worldwar2/biographies/eichmann-biography.htm

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment